Day fourteen at sea, Friday 22nd November, was New Zealand Day. Wind at 20 knots. CC Coral at 17.7 knots.

Smoke from Australia misted over my first glimpse of a blue/green shadowy landrise on the horizon. Felt some melancholy on awakening. End of trip? The beginning of no-plan? Not knowing?

A large white bird flew through my first sight from window. I hoped it was an albatross. It flew into the mist unharmed. Then there was a small white, possible tern? Another small brown. Where were the fishing vessels in all this ocean?

Up in the Bridge, the Captain gave me the run-down on the crew. Officers went to university. He studied for five years, including work experience as a deck cadet. The Able Bodied Seamen might rise to the level of Bosun but they would have to go to college to become higher officers. Engineers and deck crew were different specialisations. Captain had met some French polyofficers who were both Captain and Chief Engineer but he had heard that even the French had separated the skills.

The sun glinted off the dappled sea. The New Zealand silhouette rose and fell like a graph off to starboard. It was almost completely obscured, not by a Long White Cloud, by rusty smoke haze.

In my happy place in the quiet bow, the AB asked if I was going home. I looked out at New Zealand. I supposed I was. Home. One of them. At times I thought of myself as a pot-plant, picking up my roots and taking them with me where-ever I went. But that’s not true. I could feel the connections tighten as I approached. I could hear whispers and feel memories stir in my guts. Images played in my mind. My mother-land. Aotearoa. Tendril roots had been left in Auckland and in Dunedin at school and university. Friendship. Laughter. Love. Parents and grandparents. All here. Off to starboard.

That made Australia my fatherland and the soft green of England my birth-land. And still I struggle to put my personal puzzle in order. Even as we glide alongside my motherland I can only imagine how I would fit here.

Put on jumper and vest to stroll outside. Sat in the bow and watched NZ grow closer, still covered in the misty haze of bush-smoke.

Back in the Bridge I told Third Officer about the exciting NZ Bird of the Year competition. He was bemused. I tried to explain by telling him how proud New Zealanders were of the kiwi, one of the national emblems. But is not a kiwi a fruit? Yup. A bird, a fruit and a person. With a feathery-soft, round brown body and a long beak. The hidden bird. Well, that cleared things up. However, the Bird of the Year for 2019 was Hoiho! (Not a fruit.)

I went down to the office to meet with the Chief Engineer who took me over the threshold of the control room and down into the four-story engine space for a tour.

A small alarm sounds somewhere on the ship maybe once every couple of hours. When I’d asked Third Officer up on the Bridge he didn’t recognise them, I supposed, firstly because they had nothing to do with his bailiwick and secondly, they were part of the orchestra of sounds the ship produced.

My first impressions of the engine was clean. Mostly painted green and pale grey, the space was organised and well signposted. Basically, there were huge generators for all the power requirements and the main eight cylinder engine to power the propeller. As Chief Engineer Alin put it, much the same as your car, only there were a lot more filters.

Air was compressed, dried and heated for use in the engine for combustion. The many pumps around the engine facility include air being cooled for the essential air-co.

Water was also necessary for the engine. Ballast water was cooled in order to keep the distilled water cool to cool the engine. So to speak. Obviously you can’t use corroding salty water in a high tech engine. Distilled water was used for cleaning and showers so there’s also water heating for human use. The distillation process (water is boiled in a vaccuum at 45 degrees centigrade) left a salty brine which was sent overboard. Sewerage was also treated and after bacteria was killed the remains, deemed healthy enough, went overboard.

CC Coral used heavy fuel purchased in China. It was cleaned, filtered and heated to 120 degrees centigrade before use in the engine.

Oil was also cleaned and filtered before use. The remains were stored on board and finally used for heating or disposed of by the relevant authorities in China. The rudder was controlled hydraulically, meaning oil had to be under the correct pressure.

Around twenty main pumps kept air, fuel, water and oil circulating judiciously at the correct temperatures to keep that propeller rolling. There was only a thin wall between the engine room and the sea.

The engine room was run by computer. The engine itself could be started from the Bridge and by a manual switch on the main board. The engineers on board CC Coral did not consider themselves IT specialists but they knew enough about the program that showed them every layer of the network of pipes, heaters and condensers that made up the beating heart of this container ship. This was the factory that manufactured the essence of transport, energy to move those reevers.

I remarked to the Chief Engineer that he was in the business of keeping everything afloat. To which he responded, like a whipcrack, ‘No!’ When I stepped back in surprise at his vehemence he added, ‘Afloat is not enough. Only afloat and there will be questions.’

The Engineers agreed that electricians were now as important as the engineers themselves. Each machine was regulated and observed by sensors down to the minute detail. These sensors were the triggers for the little alarms I kept hearing. When an alarm did go off, Alin, or one of the nine men working in the department, could respond immediately, searching the screen for the disturbance. For example, when the fuel temperature rose too high, the alarm sounded and the Chief sent the Second Engineer off to examine the physical machine.

Chief supposed there would be less and less crew on these container ships in the future. Even now, the steering was largely automated. He surmised there would only be a skeleton crew to respond to physical problems such as a pipe breaking or possibly security to prevent someone making off with the reevers. The engineers worked from 08:00 to 17:00, with no-one physically in the control room over night.

It was an overwhelming visit with a lot to take in, especially while wearing ear muffs. I may have made some errors in the reporting!

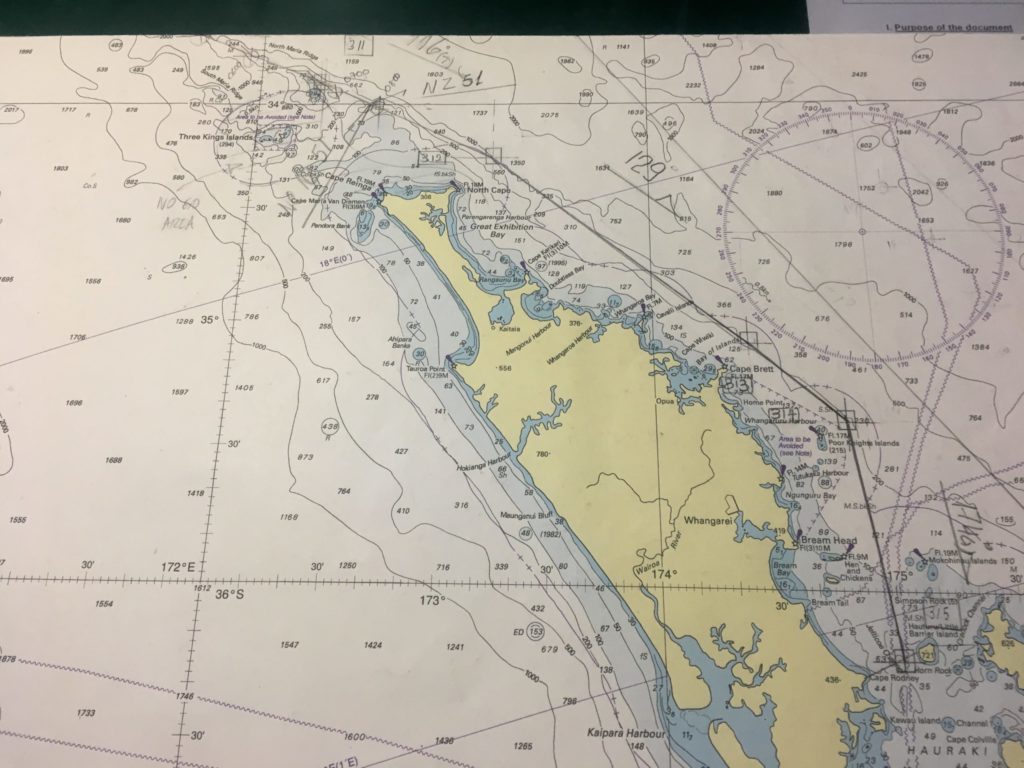

When I came back to the Bridge to see the sea and land, we were by the city of Whangarei, not visible from the sea at all. It was smooth sailing, some little whitecaps and there, some small white birds flitting easily amongst the crests.

The smoke from Australia made the sunset misty.

I believe the pilots didn’t have to swing up a rope ladder the whole height of the ship nor clamber over the side railings in an undignified manner. There was a Pilot’s Door half-way down the side of the ship so they managed their entry up the stairs with aplomb. I joined the Bridge soon after the NZ pilot came on board around 19:00.

What a different atmosphere to the day! The whole width of the bridge was curtained from the glare of computers and working lights (needed to make the coffee) behind the officers. The ship was stopped. There, in front of us, was the width of Auckland harbour in darkness. The city lights were beginning to twinkle. Car lights sprayed around the edge of the deep inky black water. Rangitoto dissolved into darkness. The pilot had his coffee. And then called for dead slow ahead.

Step by step we inched forward between the red lights to port and green to starboard. We progressed slowly and quietly through the channel as obvious as a road, once you knew where it was. For me it was a waiting game. What would happen next? Spellbound in the quiet dark. Only the pilots call and the AB’s response kept us going. Port 05. Port 10.

Those cars moving along the shore roads looked so close to the water. How will Auckland’s roads cope when sea levels rise? At one point, when we moved out to the wing deck, the pilot did admit to the Captain that this was the first ship of this size he’d brought in to Auckland. The tug was alongside much longer than it had been in Brisbane and they didn’t use a little boat to bring the ropes to the bollards. Instead three burly folk stepped up to bring the great ropes to chest height and heave them forward.

Fifty days! It had taken me fifty days from Harwich to Auckland.

Tao 50 said, ‘Emerge into life, enter death.’ Hello Auckland. ‘No mortal spot.’

I had to stay the night on board because Immigration could not attend until the following morning. After I’d left the Bridge they’d discharged one particular box that contained air bags for cars, the explosive inside them a hazchem of sorts. As I slept they’d moved the ship around the corner. Auckland really was a small port given the amount of containers that were coming off here. They would have to move the ship once more, when the ship behind them left, so the cranes could take the boxes from the bow.

Day 51: Auckland, New Zealand!

I waited for Immigration in the ship’s office. He turned out to be a very nice fellow called Paul who wistfully dreamed of visiting Spain one day. Up and down the stairs to get papers. There were three cruise ships in town so officialdom was busy. There were also a number of yachts being delivered into the harbour, can’t really say coals to Newcastle, can I, yachts being renewable energy and all …

When I went to security there was a group of four excited men waiting to be delivered to the Happy Delta – perhaps they’d get that big yacht into the water and sail away? Apparently CC Coral had a big yacht in the hold, stored across the ship. Wouldn’t have been much good in a storm, would it!

I shook most of the hands as I left. Captain. Third Officer. Messman. Chief Officer hanging on to do his handover before he jumps on his seventeen hour flight back to Romania the following night.

By the gangplank the AB wore his electric blue sunglasses shaped like mad swimming pools as he waited for the security van to show up. The immigration man came too, concerned at my ability to negotiate packs and gangplanks but I had both hands this time, and fresh gloves, ripped from the packet by the Chief Engineer. He had plenty.

Security took me to the gatehouse, where we greeted a constant stream of trucks come to take loose coal, charcoal and gypsum, the rubbish truck to take CC Coral’s rubbish (all those plastic water bottles) and I am through into the streets, highways and byways of Auckland. My dearest university friends are there to greet me with hugs, smiles and toast.

Auckland, New Zealand. Saturday 23rd November. Day 51. ‘Events form them. Energy completes them.’

Energy got me across the world. Not clean energy, perhaps, but I found different ways to avoid flying.

In conversations with my fellow rail passengers and later, people who are interested in this trip, I find most people aware that flying damages the atmosphere. Most people are aware the atmosphere is not in the best of health. Most people have at least considered carbon offsetting in their travel plans.

And I am sure you will continue to think and learn about the air we all breathe. There are no walls or borders that can stop the wind.

Up-date from Marcea in Totnes! She says: “The Transition homes are being started next year so I’m going to be trying to sell here – 23 years been here! Am making wreaths for people and fun things at the art group I volunteer at.” and a PS: “this afternoon we glue on to the council offices as they have kept their climate action plans secret when they said they’d do citizens assembly to make the plans..! Awful election results more Tory years ahead but we won’t stop ..xxx”

epic quote “As usual, the more you know, the less you know and the more I smelled.” err ! diesel fumes and the sea = roiling nausea

So happy you got the upgrade to the Owner’s. Really enjoying your experience of the high seas and can’t wait to read more!!!

Thank you for reading, KarenK, so pleased you’re enjoying the blog.

Thank you, Gelfling!

Glad you made it safe. And met new friends! So good!

Reading this, all pages, after you have been in Aotearoa NZ for just over one month. What an awesome adventure. But also conveying the sense of that disembodied vessel and its occupants chugging through the different seas.I hope you do feel that you are safely home.

“We shall not cease from exploration. And the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.”

Thank you, Pen, I am certainly in one of my homes! But I am certainly enjoying the music, scenery and of course, mainly, my good friends in Aotearoa.

Thank you, Lucy! The things I do so you don’t have to! Bon voyage to you – long and short!

Epic voyage and marvellously engaging account! So evocative, I could almost smell the fumes and feel the engines rumble. Some magical moments, poignant ones, lots of fun facts. I feel like I vicariously experienced something I would never have otherwise had the opportunity to experience. Thank you, dear, V! So many wonderful words!

Thanks, Louiselle – not sure how to take that! Here’s the link Louiselle found, showing where CC Coral is RIGHT NOW! https://www.marinetraffic.com/en/ais/details/ships/shipid:194020/mmsi:215141000/imo:9350393/vessel:CMA_CGM_CORAL?fbclid=IwAR05MwRi6hgtnJhTKbfQdyxSCHdMi3cm6SZzFCD-GrJJHHiekhNVqMAfReU

Have reread all, blooming marvelous my friend. Can’t wait to see you again, soon

Thanks, Louiselle, Absolutely! And thanks for your encouragement. Really appreciated.

Have completed page 1.. thrilled