The Sierra Nevada behind the Alhambra

My visit to Granada, in Andalucia, was too short, of course, but I was greatly impressed by the place. It was easy to see how the lie of the land created the terrible human dramas that unfolded there. One side of the valley is heavily wooded, with constant running water streamed in from the melting snow of the Sierra. That’s where the great fortress complex, The Alhambra, looms over its surroundings. The Alhambra was built on Roman ruins by Mohammed ibn Nasr, founder of the Nasrid dynasty.

Granada valley from the Abbey del Sacromonte. The Alhmabra is up to the left. You can see the ancient city wall along the crest of the hill to the right.

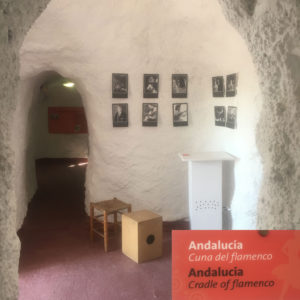

The land is dry on the other side of the river. That’s where cactus and caves are found. It’s a dramatic demonstration of power and wealth on one side of the river, and poverty, desperation and flamenco on the other.

The hills are steep. The Alhambra was well protected from invasion. It lasted three centuries before Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand got their hands on it. They are buried in Granada.

The tower of Iglesia San Pedro y San Pablo. The Alhambra is up at the top of the hill – and there’s a river at the foot of this valley. No casual visit from this angle!

What made the Alhambra’s position even more inviolable was the constant availability of water. Long term survival was possible even if besieged by the strongest forces.

Practical and decorative. All the buildings in the Alhambra centred around water and often had water inside the rooms to add tranquility and air temperature control

The medieval water channels, still delivering water around the buildings and gardens of the Alhambra, are over a thousand years old, possibly Roman ruins that lie under the Alhambra.

In extreme contrast, the other side of the river is baked by the sun into dry, hard territory. But here, people managed to scratch out a living for hundreds of years. People who were disbarred from society. People who were oppressed, expelled and hunted down to die. The Spanish royalty had ways of getting rid of those they considered undesirable and it was hard and terrible. But in the cracks and crevises of this forbidding dirt they managed to raise families and eek out a living.

And yet.

Is it not strange that, when today’s daily 7,700 visitors enter the grand palace at the Alhambra, they walk into man-made caves?